![Banner [Workshop] Facebook](https://rmibogor.id/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Banner-Workshop-Facebook-3-1024x537.png)

Research Dissemination on Pre and Post Recognition of Customary Forests in Indonesia

Friday (30/11) RMI disseminated learnings of research on the recognition of customary forests to relevant stakeholders. The research supported by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has been carried out for the past year by RMI together with several members of Koalisi Hutan Adat (Customary Forest Coalition) consisting of HuMa; Bantaya, Central Sulawesi; Yayasan Merah Putih, Central Sulawesi; AMAN, South Sulawesi; Q-bar, West Sumatra; and LBBT, West Kalimantan. The dissemination of the research’ findings conducted at Century Park Hotel, Senayan serves as an input as well as a push for the acceleration of customary forest program as a part of the larger framework of the recognition of Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia, which currently is the major focus of related CSOs and government agencies. This acceleration process is in the same vein with Government’s efforts to recognize Customary Forests of Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia. In accordance with the title: Learning from the Pre and Post Customary Forests Recognition in Indonesia, this research presented various lessons-learned from seven Indigenous Communities that have experienced administrative processes of obtaining legal recognition of their fustomary forests, which five of them have succeeded in obtained and two others are still in the process of obtaining the recognition. This research is aimed to provide learnings for Indigenous Peoples in the same struggle, as well as to inform decision-makers in regards to the process experienced by the Indigenous Peoples communities for this purpose.

The seven Indigenous Communities are chosen based on a combination of contexts and conditions as such that the pre and post recognition of customary forests can be comprehensively represented. The contexts that are considered in selecting the subjects -and at the same time the location of the research- are: geographical representation (representing major islands in Indonesia); stages of the process of Customary Forest recognition (already recognized or in progress); state forest category where customary forest is located (conservation forest, protected forest, production forest, and / or non-state forest area); and the status of sectoral regimes that control the area (conservation, plantations, and / or mining).

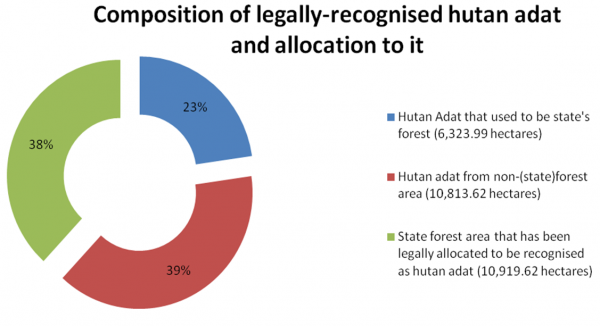

In the first half of the event, pre-recognition processes of the seven Customary Forests are explained and discussed in a talk show that presenting various stakeholders. An interesting fact presented by Nia Ramdhaniaty as one of the research backgrounds was on how the area that has been recognized as Customary Forest by the government to date, are largely located in non-(state)forest (commonly referred to as areal penggunaan lain or APL). Of the total of 17,243.61 hectares (ha) that have been recognized in 33 Indigenous Communities in seven Provinces, only 6,322.99 hectares were excluded from state forests status, whilst the remaining 10,919.62 Ha (63%) recognized Customary Forest are located in APL. This shows how the recognition of Customary Forests are not in relevance with the spirit of the Constitutional Court Decision No. 35 / PUU / X / 2012 (MK 35) which excludes Customary Forests from the status of State Forest. The research team also found that the current rate of Customary Forest recognition, that is 11 Customary Forest per year, would provide long journey up to 196 years to be able to recognize some 2,000 Indigenous Peoples communities in Indonesia. The latter is identified by their membership in the Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN).

An important finding in the pre-recognition of Customary Forest which is also one of the recommendations of this research is related to the contestation of paradigm regarding “Customary Forests” itself, between the communities and the state (represented in the policies). For Indigenous Communities, the customary forest is a conception of space which is a supporting ecosystem for life and livelihood, including the resources contained such as food, energy, religious, social, economic, ecological, cultural, educational, and health, which is managed based on customary rules and implemented hereditary. Customary Forests stated as a category of Forest which only defined as an ecosystem unit with certain functions that must be maintained and characterized by tree formation. The recommendation is to follow-up by adjusting the terms and meanings of Customary Forests stated in each recognizing Ministerial Decree in accordance with the terms and meanings of the customary forest lived by the community. This research proposed different presentation between the state’s understanding of Customary Forest (i.e. with capital C and F), and customary forest according to the indigenous people communities that have different forms and meanings (no caps).

In the first talk show session, Director General of Natural Resources and Ecosystem Conservation of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), Wiratno expressed his support for the Customary Forests acceleration program. His statement responds to two research findings states 1.) the administrative process of recognizing Customary Forests in conservation areas takes longer than in other areas, especially APL; and 2.) that recognition of Customary Forests that were located in state conservation forest only occurred in the first wave of stipulations in 2016, and there are no state conservation forest converted back into Customary Forests ever since. “In the conservation area, the work-flow is in sync with the PSKL (General Directory of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership of MoEF). It will be further adjusted and I think Customary Forest recognition in the conservation area is not a problem,” he said. Meanwhile, an expert on national forestry policy from Bogor Agricultural Institute, Professor Hariadi Kartodiharjo pointed out the need for more affirmative protection for Indigenous Peoples’ communities by means of a legalized Indicative Map of Customary Forest in the form of Ministerial Decree. According to him, “if we can have an indicative map of forest permit given to corporations/companies, why not with the Indicative Map of Customary Forests?”, it needs to be done immediately because the situation on the ground is rapidly changing, non-administrative approaches are largely exercised for capital interests while in the case of Customary Forest, the administrative aspects are the obstruction.

On the same occasion Dahniar Andriani, Koalisi Hutan Adat’ Coordinator from HuMa highlighted that MK 35 and lessons learned from the pre-Customary Forest process in this research have been a trigger, opening the discussions on the chaotic agrarian law in Indonesia since the Dutch Agrarian Law (Agrarische Wet 1870). She explained that this contradictory laws and regulations in regards with Indigenous Peoples rights’ recognition can be felt through various conditional and different requirements stated by different regulations that have made this legal Customary Forest recognition became full of obstacles and very slow in its implementation. She further explained that the Indigenous Peoples Act needs to be ratified immediately for a uniform and integrative concept of Indigenous Peoples, hence their rights fulfillment.

The second and final half of the event discussed the conditions and developments after the recognition of customary forests within the seven locations. During the presentation by Mardha Tillah, two of the most dominant things observed after the recognition of customary forests are the increased security regarding livelihood resources, as well as increased in authority and opportunities in terms of managing indigenous territories which led to the development of the community’s economy and even the revival of traditional forest management systems. As an example is how the young generation of Indigenous Communities whose customary forests have been recognized are starting to (again) wear their traditional clothes proudly, and how the community in Kajang community can decide for themselves the use of their forest area which has long been the object of dispute with PT. London Sumatra, a private rubber plantation company that has presented there since the 1910s. Another important thing that developed after the recognition of customary forests is the opportunities for greater participation of youth and women groups in the area of forest resources management. Although it still needs to be further addressed, this finding shows how the recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples is also an affirmative step for marginalized groups in society. Additionally, she reminded the findings of the research that pointed out the negligence of various government bodies to follow up, for instance, the revision of State Forest Map that should have excluded the legally-recognized Customary Forests that has not taken place. Therefore, although the President has mentioned that there would be a new map label in State Forest Map namely Customary Forest with specific color-code, however, this can be found nowhere in the map today.

Regarding the follow-up after the recognition of Customary Forest, Bahrunsyah, Expert Staff on Customary Affairs of the Ministry of Spatial Planning and Agrarian (MoSPA) who was one of the speakers stated that one of the entry points to the MoSPA support is the MoSPA Ministerial Decree No. 10 the year 2016 on Procedures for Determining Communal Rights on Land of Indigenous Communities and Communities in Specific Areas. This can be done, according to him, by including integrating Customary Forest spatial planning into RTRW (smallest spatial administrative unit) at the Regency and Provincial level. “MoSPA wants to accommodate mapping and boundary identification. I hope after the recognition of Customary Forests there will be a systematic land registration,” said Bahrunsyah. The Ministry of Village, (MoV) represented by Sri Wahyuni said that the Village Fund program could be a means of economic improvement for Indigenous Communities who are supposed to have equal rights compared with villages as an administrative governance unit. Even so, there was no concrete response regarding the opportunity to empower Indigenous Communities after the recognition of Customary Forests which could be facilitated by the Ministry of Village.

Meanwhile, Yon Fernandez from the FAO Indigenous Peoples Team saw more opportunities ahead in the recognition of Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia. For him, exchanges of learning at the global level are important as good practices in South America and even India who have been able to provide millions of hectares of forest to Indigenous Peoples. According to him, the same thing should be possible in Indonesia. Another important thing highlighted by Yon is how the recognition of Indigenous Peoples as a subject is no longer needed because it has been explicitly stated in the Indonesian Constitution 1945 (UUD 1945), what actually needed for a more meaningful recognition is to legally recognize the relations between Indigenous Peoples as subjects with their objects of rights. The locus of the identity of Indigenous Peoples identity is precisely within their relation to their territories, their living ecosystem, which are objects of their rights. Therefore, subject legitimization of Indigenous Peoples at the regional level in the form of Regional Regulations is actually absurd and not needed. (WF)